120 years of learning and growing has yielded massive change — even in the very mission of SHS.

Sitting in a bustling diner on the rolling hills of the Palouse, 83-year-old Nona Hengen becomes childlike again. Remembering small details from a big day a long time ago, her face brightens, creasing into a pleasant smile. She’s telling about her first memory of the Spokane Humane Society.

“I was seven or eight years old, and we visited the old Humane Society location near the Flour Mill,” she says. “I can remember the excitement because we had come to adopt a dog.”

That early-1940s day remains strong in Nona’s memory, though it’s been decades since the society moved and the cubical brick building at 704 W. Broadway was razed in favor of a parking lot. When it was new in 1910, the building was alive with stables full of stray livestock, and served as a hub for the fledgling SHS’s Humane Officers to convene, sharing stories and ideas of how to protect horses from abusive owners and injuries.

After the first World War, a time-lapse video outside the still-new facility would show the gradual transition from horses to automobiles filling the dusty brick Broadway Avenue, including that of the “dog-catcher,” whose exploits were dutifully (sometimes a bit sensationally) recorded in the Spokesman-Review. When Nona left the SHS that day during the second World War, she left with a “mutt of the Airedale type,” and, of course, with the unmatched joy of a child with a new pet.

“I was seven or eight years old, and we visited the old Humane Society location near the Flour Mill,” she says. “I can remember the excitement because we had come to adopt a dog.”

But while she was there, one can imagine that gleeful little girl walking past the elegantly dressed Agnes McDonald, or having her hair tousled by W.S. McCrea, a towering, silver-haired man in a three-piece suit. Maybe a smile from a quiet, much younger employee named Norman Finch.

Roughly fifty-five years later, Nona would capture the stories of these early pillars and their leadership at the Spokane Humane Society in her book In Pursuit of Compassion: A Centennial History of the Spokane Humane Society 1897-1997. Conceivably, any or all of them could have been present on Nona’s first adoption day — the first of many, many dogs or cats she would acquire from SHS, taking each home to the same farmstead in Spangle, Wash., where she lived at age 7, and still lives today.

That most basic experience of adopting a pet is the way thousands upon thousands of people have interacted with the Spokane Humane Society. But the organization’s 120 year history encompasses a stunning range of activity and a long list of compelling characters whose vision shaped the Humane Society, and whose dedication sustained us to become one of Spokane’s oldest charitable organizations. Thanks to Nona, these stories are known.

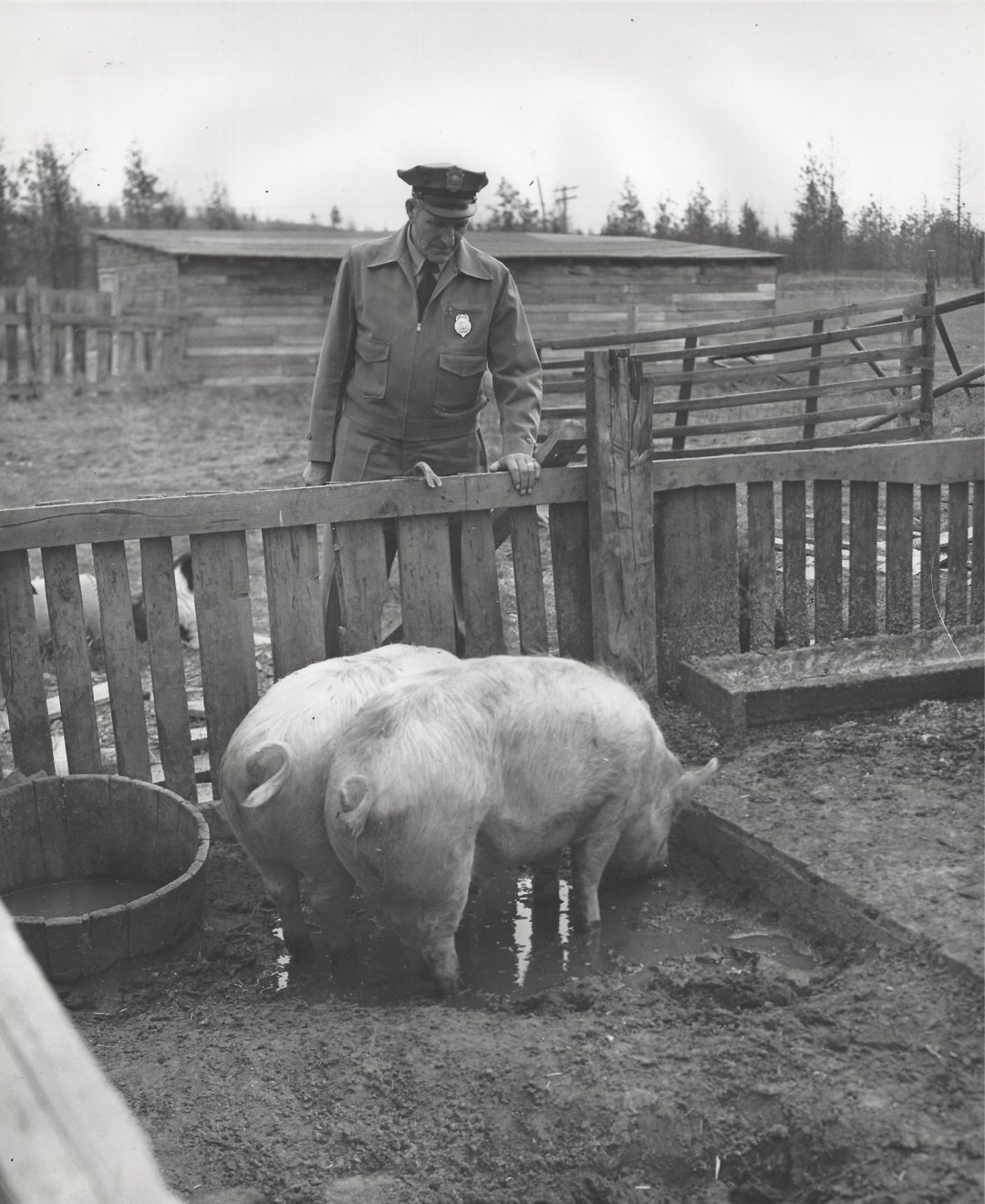

We know that, prior to World War One, Spokane Humane Society focused on the treatment of horses and even orphans — the latter because the new city hadn’t yet built the infrastructure to adequately care for children in need. As for the horses, the Spokane Falls streets were teeming with them, often carrying heavy loads from the rail yards out and up to the “Addition” neighborhoods that were being built. Humane Officers like Agnes McDonald watched for overburdened or abused horses, and were even deputized to make citizens arrests. SHS provided key input on the use of sand to prevent horses from slipping on the streets and breaking their legs.

In the 1910s through the Great Depression, as horsepower gave way to automobiles — and the needs of children began to be met by other government and private agencies — Spokane Humane Society’s focus shifted to dogs. Hengen tells stories of directors like Joe Rudersdorf and others working to transform a chaotic and unhealthy feral dog population freely roaming the city into a healthy, contained, and licensed population living harmoniously with humans.

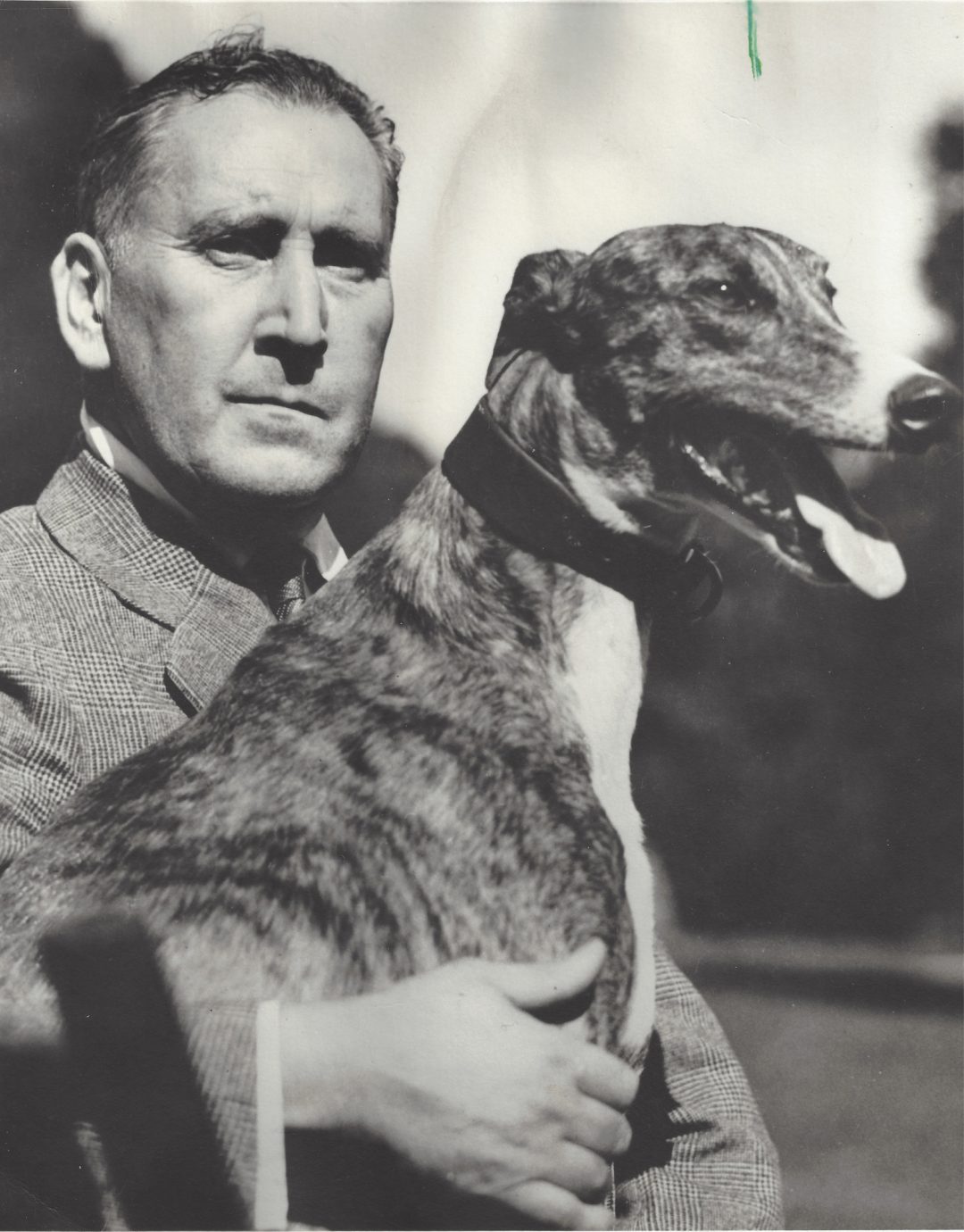

We know of the mid-century figure Norman Finch, a quiet and compassionate man who began at SHS as a night janitor and went on to a legendary 38-year career, diligently advocating for animals up until his death in 1974. Shortly before passing away, Finch saw the groundbreaking of the north Havana location, where the organization thrives today.

We can look back over the Humane Society’s transitions in roles, priorities, and practices, but through this tapestry runs one common thread: of love, plain and simple. Love that prevents cruelty and promotes health and companionship between the people of this city and the animals with whom we live and work.

Late century leaders like Diane Rasmussen wrestled openly with the heart-wrenching aspects of caring for animal welfare, fighting as hard as possible to reduce the number of animals that would need to be euthanized, through active spay and neuter campaigns and the promotion of adoptions, fueled by the undying belief that, for each pet, there is an ideal home.

Today’s vital onsite veterinary clinic at SHS and the recent movement to never euthanize an animal due to a lack of space are due to the often quiet underlying characters in the story of SHS: the donors and volunteers who, for well over a century, have carried the mission of the organization on their backs.

In a recent conversation, the now-retired Rasmussen said, “We have been here 120 years because of giving. People have given of their time, their money, and their hearts.” Her tone seemed to imply, even a bit urgently, that a new generation of givers and servers and lovers of animals must come forward for the next 120 years of the SHS story to commence.

She has told the story and loved the animals; she has talked the talk and walked it. As she finishes sharing old tales, it’s easy to wonder whether there might be a young girl right now out on Havana, bouncing around the facility with wide eyes, choosing a new best friend and beginning a lifelong story of advocacy.

Back at the diner, Nona continues to tell story after story, from individual cats to influential donors, but it is easy to sense that her love for the animals and the broader mission of the SHS is outpacing her energy to participate.